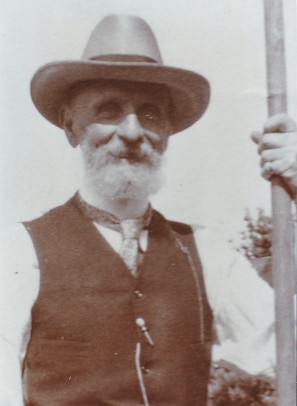

The Story of Colonel Francis Weldon, the first occupant of 153 Wokingham Road (now owned by Earley Christian Fellowship).

Irish Roots

Francis was born in 1836 at Rahinderry, Queen’s County (now Co. Laois) in Ireland. He was the sixth son of Sir Anthony Weldon, a Baronet. Anthony was the son of Rev. Anthony Weldon of Athy, and when he was only fourteen he joined the East India Company and was not heard of again for thirty years. When he returned he found that not only had he inherited a baronetcy on the death of his cousin William, but also a grand house called Kilmoroney, built in 1780, on the death of his cousin Stewart. However, because of his absence, he was believed to be dead and the house had been given to another man, Rev. Trench, for his lifetime. By 1860 when Rev. Trench died Sir Anthony had also passed away in 1858, so the property of Kilmoroney passed to Francis’ eldest brother, Sir Anthony Cresdill Weldon, 5th. Baronet Rahinderry.

Today only the crumbling ruins of Kilmoroney House remain. It is a broken, roofless derelict shell outlined against the skyline. Originally it was a two storey, five bay Georgian house of grand proportions with a balustraded roof parapet. Kilmoroney is situated on a bend of the River Barrow and travelling from Athy the river had to be crossed a quarter of a mile from the house. There was no bridge across the river and a large float was used to carry carriages and horses across. From the river the ground in front of the house rose gently, the drive first passing a wooded area on the left. Kilmoroney House and the land on which it stood was to remain in the possession of the Weldon Family until 1934 when the then Lady Weldon moved to Dublin following the death of her husband, Sir Anthony, 7th. Baronet, in 1931. A public auction of the contents of Kilmoroney House was held that year and many of the valuable artefacts accumulated by generations of the Weldon family were dispersed.

As for Rahinderry where Francis was born, little remains of the original, any remaining buildings having been given over to farm use. But there is an avenue of excellent rare oak trees neatly spaced at 80 yard intervals, perhaps planted to commemorate the birth of Francis, or more likely his eldest brother. The beautiful trees and the distant view of the Wicklow hills are all that remain of what Francis would have known.

By the Second World War, Sir Thomas Weldon, 8th, Baronet, who by now was living in England, found himself unable to take up occupation again in Kilmoroney House. The Irish Land Commission took over the land and the magnificent Georgian House was soon to fall into ruins. This was the fate of many grand houses in Ireland following the upsurge of anti-British feeling in the 1920’s. The government acquired these estates and gave only “Land Bonds” of meagre value in exchange.

The Accident

Francis was fifteen when he had an accident that could have been the end of all his ambitions. He was a boarder at Mr. Thomas Arthur’s Huguenot school at Port Arlington, Ireland, when one Sunday afternoon he and another boy decided to pay an illicit visit to the girls’ school nearby. He climbed up and over the wall of the school but while he was helping his friend up the coping stone gave way and stones and the other boy fell on top of him, badly crushing his knee. The alarm was raised, the local doctor called and it was decided that the injury was so bad that Francis’s leg would have to be amputated.

The operation would have to be performed in Dublin, so Francis was put on a barge with his father and travelled down the River Barrow and the Grand Canal to the capital. But on the day of the operation a thick fog descended, quite unusual for the city, and as the oil lamps of the period proved ineffectual in giving enough light for the surgeon to proceed, the operation was postponed to the following day.

At dinner that evening at the Shelbourne Hotel, his father was introduced to an eminent English surgeon who was on holiday. When he heard of the distressing circumstances of Sir Anthony’s visit, his compassion was aroused. He asked to see Francis and as a result of the treatment he prescribed, the patient was sent home with both legs. Francis never went back to school in Port Arlington, but over the course of the next few years, using crutches, he gradually learned to walk again. He recovered so completely in fact that his medical certificate for the East India Company states “he is without deformity and has the perfect use of all his limbs”.

India

Francis’ family was an Army family and it was probably assumed without question that he would go into the army too. His brothers Anthony, Walter and Thomas were all high ranking officers in the Indian Army.

So Francis prepared for the entrance exam at the University of Military Institution, Talbot Place, Dublin. His father decided to take him to London in 1855 for the examination for cadetship, but wrote on 28th. July to the authorities, “I regret extremely that instead of accompanying my son Francis, about whom I wrote to you as having been appointed a Direct Cadet to Madras, instead of accompanying him myself and introducing him to you, I am obliged from ill health to forego that pleasure, and send him under the charge of my eldest son, Lt. Weldon who I have no doubt however can take good care of his Brother … I had actually left home for London a few days ago and have been obliged from a severe attack of illness to return.” Francis probably never saw his father again.

In 1856, Francis sailed to India on the ‘Devonshire’. Amongst their other activities the cadets took their share in pumping out the ship to the shanty ‘Way my boys and up she rises, early in the morning’. He was also selected for special mention by Major John Crisp who wrote to the Military Secretary “The need however of unqualified praise and approval is due especially to Mr. Weldon and Mr. Tullock. The conduct of these two gentleman has been uniformly most exemplary. Besides maintaining their social positions to my entire satisfaction they devoted their time largely and systematically to the study of the Native Languages. Mr. Weldon having acquired a considerable knowledge of the Hindoostanee and Mr. Tullock both of Hindoostanee and Tamil.”

Francis was a first rate horseman and a first class shot and with an exceptional ability for games he soon made his name. He rode winning horses, secured the coveted South India Racquet Handicap in 1860 and as a shikari (Urdu for hunter), he tracked and shot seventeen tigers besides other game. His first commission was in the VI Madras Native Infantry. He transferred to the Cavalry and eventually commanded the Nizams Hyderabad Contingent.

In 1871 he took his first leave and the account of that triumphal homecoming made headlines in the Kildare local paper.

In 1872 he married Henrietta Kennedy, ten years his junior, whose family, also Irish, had a long connection with India. Theirs was a lifelong partnership of devotion and happiness. Henrietta was a true helpmate and Francis owed much to her constant encouragement and comradeship, for he was naturally diffident, extraordinarily modest about his abilities and devoid of any personal or worldly ambition, although when any question of principle arose he was as fearless as a tiger.

They returned to India and their first two children, Walter and Ethel, were born there. It was during his service in India that Francis took up the scientific study of Range Finding, and in 1875 on the advice of the Adjutant General of the Army at H. Q. Mahableshwar he was sent home to enable the instrument he had invented to have authoritative tests with a view to its being officially accepted. The Weldon Rangefinder was approved and shown at various Exhibitions. It was during this time that their son Ernest was born in London.

Francis served in India during the Mutiny, and then in 1882 he came back to England at the request of the War Department in order to develop the use of the range finder and to give instructions in its use to soldiers at Aldershot. It was still being used by the army in 1926. In 1884 his daughter Winifred was born, and two years later Evelyn. By this time Henrietta and Francis, now Colonel Weldon, were living in their newly built house Erlimount, then numbered 127, Wokingham Road, Reading.

Still inventive, though no longer on active service, Francis, in his fifties became interested in Military Bridging, and he designed the Weldon Trestle Bridge, used in active service in the Boer War and the First World War. In his lifetime there was a model of the bridge in the grounds of Erlimount.

Erlimount

By 1891 there were ten people living at Erlimount. Francis, Henrietta, Walter (who was a student at Cambridge), Ethel and Ernest, (both at school), Winifred (aged 7) and Evelyn (then aged 5, but who died two years later). The household also included the elderly Anne Lane, born in Devon, a much-loved nurse to the children and companion to the parents; Marie, a young Swiss woman employed as a nurse; and Henrietta, a local girl who was the parlour maid. At number 128 lived Thomas and Harriet Jackson the gardener and cook.

The grounds of Erlimount were extensive. There was a meadow or field which extended to Auckland Road where there was a gateway opposite. The field was home to the horse, presumably enjoying retirement with the advent of the motor car, as the coach house soon ceased to house the coach. After the gateway was an 8ft. high wall as far as Adelaide Road. (Part of the wall still remains). Behind the wall were the gardens and orchard for the house. In the garden was a giant swing which the Colonel had invented.

In the course of many summers the swing was a delight to thousands as Children’s Missions run by Cliff College students were held there. The students went to Anderson Baptist Chapel to advertise the meetings. No doubt the swing was the biggest attraction. A marquee on the lawn and the coach house were used for the activities. Francis was a man of faith. He was often described by his soldiers as a keen Christian soldier. He was keenly interested in many evangelical associations including the Bible Churchmen’s Missionary Society, the Irish Church Missions and the Church Pastoral Aid Society. He attended Greyfriars Church in Reading. His daughter Winifred wrote after his death that “throughout his long life he was upheld by the strong religious faith which shone with the radiance of the sun through a many coloured stained glass window”. Perhaps she was thinking of the window on the front of Erlimount. In his den, the room with the pointed window above the front door, Francis wrote letters with his characteristic wit and good prose, and books on military, philosophic and religious subjects. The title of one book, now in the British Museum, is “Pyramidic Witness to Veiled Knowledge”.

By 1906 Francis though getting on in years was still remarkably fit as was witnessed by amazed and delighted guests at his seventieth birthday party, on 30th. July when he accomplished an unique pole jump much higher than his own height. A tribute to the surgeon who saved his leg so many years before.

At the outbreak of the First World War, Francis’ son Ernest was actively engaged with the Dorset Regiment as a Major. He was wounded at Sulva Bay and mentioned in despatches. Francis himself saw the maimed men returning from the trenches and his deeply sympathetic nature was stirred by the sight of crippled young soldiers. Knowing their plight from his own youthful experience he determined do something to help them, and invented the ‘Weldon crutch’. When the King and Queen visited the Reading War Hospital his Majesty was shown the special crutch and paid tribute to Colonel Weldon’s genius.

Epitaph

In 1922, Henrietta died. Francis lived for another four years with Ethel, his unmarried daughter, the only one of his children still at home. Ethel wrote a cantata, called “Sisters” which is in the library at Reading University. It is a combination of recitations and hymns to be used to graphically portray the plight of women in India and China, for performance at missionary exhibitions. Herein are depicted the Indian widow, the child bride and the Chinese mother, each helpless and ignorant of the gospel.

On 24th. June 1936, just before his 90th birthday Francis died. At his funeral at St. Peter’s, Earley soldiers lined the pathway from the lych-gate to the church door, and on the coffin, which was covered with the Union Jack, were Colonel Weldon’s shako and sword.

It was characteristic of this godly man that on his tombstone is inscribed “As for me and my house, we will serve the Lord”. And also that he used to write his autograph under the quotation,

“knowledge is proud that she has learned so much

wisdom is humble that she knows no more”.

Postscript

After Colonel Weldon’s death his daughter continued to live at Erlimount by herself, though as the house was sold by auction a few months after the funeral it is a bit of a mystery how she did this. By 1941 she must have been having difficulty surviving financially as she turned the house into a private hotel, perhaps a rather select one with a few elderly ladies like herself.

We do not know when Miss Weldon died or where she was buried, but by 1952 the house was a commercial hotel owned by Mrs. Robinson and boasting “hot and cold water, T.V., two lounges and a car park”.

By 1958 the house had changed ownership again and had become a hostel, run by nuns, for Roman Catholic Students at the University in nearby Whiteknights Park.

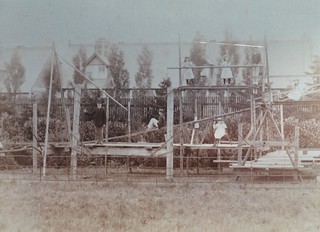

Finally in 1978, Erlimount, now numbered 153, Wokingham Road was bought by Earley Christian Fellowship along with the smaller house on the same site, perhaps the former coach house. The numbers attending increased such that in 1991 the Fellowship built a new meeting hall in the grounds.

Colonel Weldon’s chosen text had become prophetic. “As for me and my house, we will serve the Lord”.